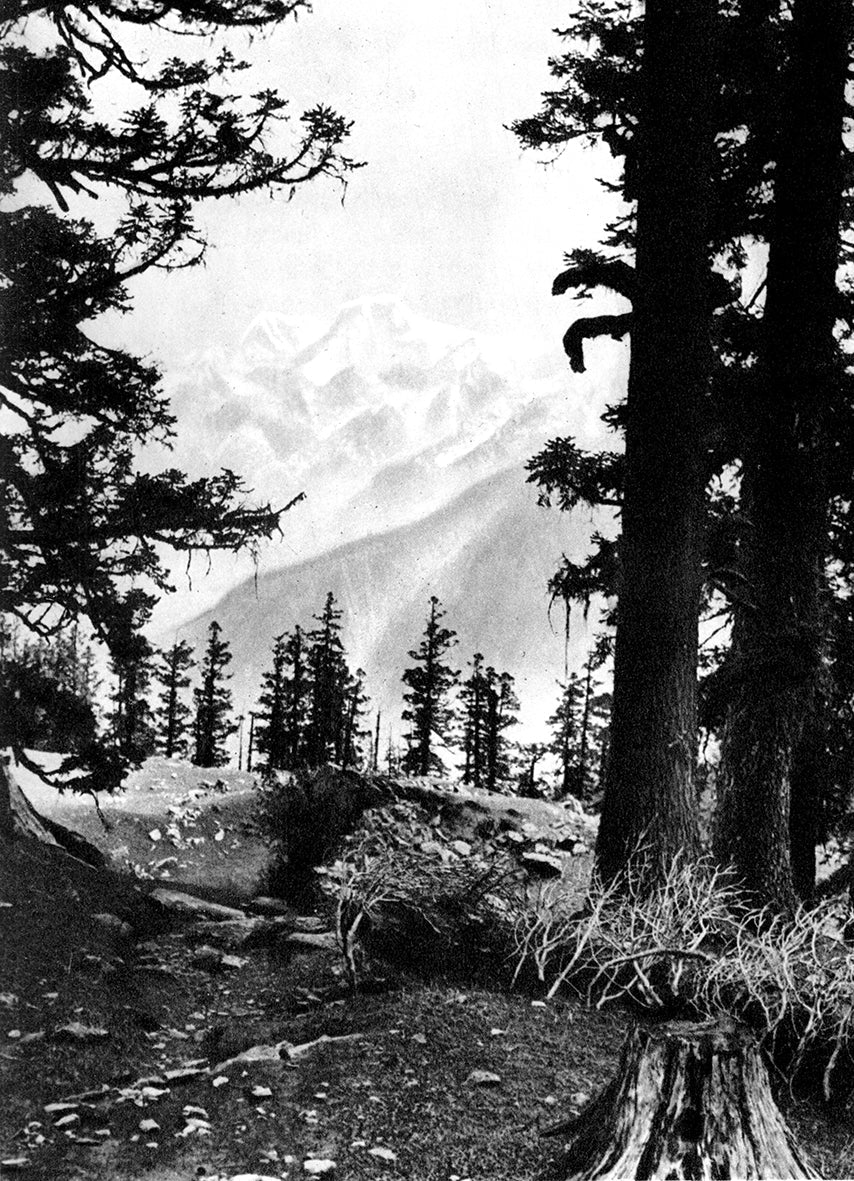

The ascent of Nanda Devi, conquering India's second highest peak.

Posted for Vertebrate Publishing - to mark the re-release of H.W. Tilman titles

H. W. ‘Bill’ Tilman was one of the greatest adventurers of his time, a pioneering climber and sailor who held exploration above all else. He made first ascents throughout the Himalaya, attempted Mount Everest, and sailed into the Arctic Circle. For Tilman, the goal was always to explore, to see new places, to discover rather than conquer.

In 1934, after fifty years of trying, mountaineers finally gained access to the Nanda Devi Sanctuary in the Garhwal Himalaya. Two years later an expedition led by Tilmanreached the summit of Nanda Devi. At over 25,000 feet, it was the highest mountain to be climbed until 1950.

The Ascent of Nanda Devi, Tilman’s account of the climb, has been widely hailed as a classic. Keenly observed, well informed and at times hilariously funny, it is as close to a ‘conventional’ mountaineering account as Tilman could manage.This extract relays Tilman’s version of events during the expedition’s journey through the Rishi Gorge.

The pilgrim season was in full swing and Joshimath was alive with devotees of all ages and all classes, men and women, rich and poor. To an outsider their demeanour gave the impression that this pilgrimage was more of a disagreeable duty than a pleasure, that the toil and hardships of the road were supported with resignation rather than accepted joyfully as a means of grace—incidents on the road to heaven. But this downcast air may rightly be attributed to the awe and terror which most must feel in the presence of such strange and prodigious manifestations of the power of the gods. Savage crags, roaring torrents, rock-bound valleys, hillsides scarred and gashed with terrific landslides, and beyond all the stern and implacable snows—all these must be overwhelming to men whose lives have been passed on the smug and fertile plains, by sluggish and placid rivers, with no hill in sight higher than the village dunghill.

Nor is it remarkable that they should attribute the faintness felt in the rarefied air of Badrinath and Kedarnath to the influence of superhuman powers; or believe that the snow wreaths blowing off the Kedarnath peak are the smoke of sacrifice made by one of Siva’s favoured followers, or that the snow banner flying on Nanda Devi is from the kitchen of the goddess herself.

The accomplishment of such a journey by such men must be a tremendous fact in their lives, something to remember when all else has faded. To reach the temple alone is a sign of divine favour, for the gods turn back those with whom they are displeased. The daily exercise, the months of frugal living, the hill air, the sacrifice of time and money, all these must play no small part in the moral and physical regeneration of the pilgrims; and if this salutary discipline of mind and body were to be enjoyed there would perhaps be the less merit. For the mountaineer, it is to be feared, though he penetrate to the ultimate sanctum sanctorum of the gods, there is, like the award of the Garter, ‘no damned merit about it’—his enjoyment is too palpable.

By midday of June 6th the telegraph line to Badrinath was working and an exchange of telegrams brought the good news that the porters would be down next day. Meantime our 900 lb. of food was ready, half here and half at another village, so that all was set for a start on the 8th, and only a day had been lost. In the perverse way the weather sometimes has, both of these days spent sitting idle in Joshimath were gloriously fine.

Fourteen men from Mana arrived in the evening, among whom were three who had accompanied us in 1934, and on the 8th we did a short march to Tapoban, where the balance of the food was collected and three more local porters enlisted. One of these men, hailing from Bompa, a village higher up the Dhauli, was an amusing character. His name was Kalu and he had chits from previous expeditions in which he appeared to have distinguished himself by going high on Trisul. He was a shameless cadger with an ingratiating manner, and a habit of placing both palms of his hands together as if in prayer whenever he spoke to you. As a mountaineer he thought no small beer of himself, particularly if the conversation should turn to Trisul as it always did if he was taking part in it, and then he would slap his chest like a gorilla, and cry out in a loud voice what great feats Kalu had performed and what greater he was about to do. For all that he worked so well on this trip that at the end I placed too much faith inhim and was let down.

At Tapoban we had a fortunate meeting with two British officers out on a shooting trip, who invited us to use their camping ground and join their mess, an invitation we were not slow to accept, as I knew from previous experience that on these shooting trips the doctrine of ‘living on the country’ is not carried to extreme lengths. But for this chance meeting and the existence of a hot spring, Tapoban would have left nothing but evil memories. The flies were unusually fierce, and as soon as they stopped work at dusk the midges began, and at dawn the reverse process took place.

The hot spring I mentioned is up a little side valley a couple of hundred yards from the road. There is a stone tank about ten feet square and three feet deep, into which gushes a stream of water at a temperature of about 90 degrees. The water is clear and sparkling, and has no taste. Close by is a shrine and a hut for its guardian, an emaciated hermit whose hair reached almost to the ground. On this occasion he was absent and we could lie in the bath at ease, increasing the pleasure by running a few yards to a brook where the water was as cold as the bath was hot, and smelt deliciously of wild mint.

A more detailed description of our route may be left for the moment; sufficient to say that after one more vile night of midges in the warm valley we began the climb to the 14,000 ft. pass where flies and midges ceased from troubling. On our way up we met a flock of sheep, and the shepherd was understood to say that one of his sheep had fallen over a cliff and it was ours for the carrying. The Mana men soon found it, skinned it, and went on their way rejoicing; it certainly looked fresh enough, but there was suspiciously little sign of it having suffered a fall. In camp that night when Loomis and I had, after some argument, come to a decision about the respective merits of grilled chops and boiled neck, the inquest was resumed, and we were calmly informed that the sheep had died through eating a poisonous plant. Somehow or other mutton chops ceased to allure and we generously gave our share to the Sherpas. I should hesitate to accuse them of using this stratagem to bring about such a desirable result, but they showed no reluctance to accept fortune’s gift and suffered not the slightest ill-effect.

We crossed the pass, now clear of snow, and got down to the Durashi grazing alp. There were no sheep there and we had the place to ourselves, the Mana men finding shelter in some caves, ourselves under the tarpaulin, and the Sherpas in a stone hut used by shepherds. It required a certain lack of imagination to sleep in this hut, because the roof of enormously heavy stones was only supported by some singularly inadequate pieces of wood, one of which was already cracked.

We woke to a wet morning and did not leave till nine o’clock, though this was not much later than usual, for the Mana men are very independent and dislike being hurried. After a leisurely breakfast, the pipe (they had only one) would be passed round several times before they even thought of hinting at a readiness to begin packing up, and unless there was some urgent reason for an early start it was useless to try and hurry them. It was the same on the march; they knew how far they were going and took their own time getting there, sitting down whenever they felt the need for a pipe, which was frequently, and remaining there till all had smoked enough.

Find out more about the Tilman Series here

![Filoment Hoody [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/AW25-Chamonix-JW-5042_2.jpg?v=1765566497&width=768)

![Heiko [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/Heiko-Men-Location-1.jpg?v=1767294910&width=768)

![Jura Mountain Smock [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/jura-mens-2025-alder.jpg?v=1765393634&width=768)

![Jura Mountain Smock [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/jura-mens-2025-alder-1.jpg?v=1765393634&width=768)

![Katabatic [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/Katabatic-men-2.jpg?v=1764529367&width=768)

![Solace [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/mens-solace-2024-alder.jpg?v=1763752169&width=768)