Seven Climbs - Finding the Finest Climb on Each Continent by Charles Sherwood

This is an extract from the book 'Seven Climbs - Finding the Finest Climb on Each Continent' by Charles Sherwood. Available on Vertebrate Publishing

Experienced climber Charles Sherwood is on a quest to find the best climb on each continent. He eschews the traditional Seven Summits, where height alone is the determining factor, and instead considers mountaineering challenge, natural beauty and historical context, aiming to capture the diverse character of each continent and the sheer variety of climbing in all its forms.

We were up with the light. Huddled next to us were the forlorn, exhausted bodies of the British pair, John and David. We tried not to disturb them, but that wasn’t easy as we dragged the haul bag across the ledge. Another traverse right required Andy to be lowered off into a crack system so he could resume upward progress and then return left, again rolling two pitches into one. I in turn lowered Max out, who jumared the haul line and then set about pulling up the haul bag, with the portaledge and poop tube attached. Finally, I bade farewell to my tired compatriots and lowered myself off the ledge, which was made easier by a fixed line trailing from the bivvy site.

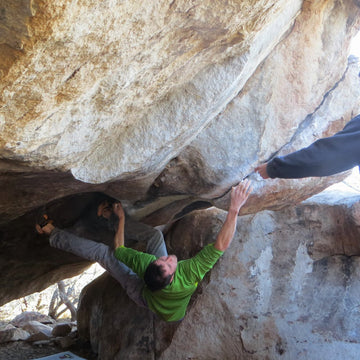

There were no hiccups. We were finally getting the hang of this. One further, uneventful pitch brought us to El Cap Tower, a roomy ledge with space for six. Andy had floated this as a possible objective for the day, but we were now humming, and there was no serious question of stopping there. Next came the Texas Flake, a huge upright chunk of rock with a gap behind it that separated it from the rest of the cliff. Andy, as leader, had to climb this narrow gap, bridging between flake and mountain, feet on one, back to the other. Only it wasn’t as narrow as he would have liked. Either that or his body wasn’t as long as he would have liked. Anyway, his verdict was, ‘SCARY!’

We dutifully followed to a belay on the top of the flake, perilously balanced with a drop on either side. Flakes were the order of the day: the following pitch was the Boot Flake, a remarkable bootshaped feature that the Duke of Wellington would have been proud of. And having surmounted that, we were at last positioned for one of those great moments in a climbing lifetime: the King Swing.

How Warren Harding figured this out in 1958 beats me. Yet he knew he needed to complete a big traverse back left, and reckoned the only way that could be done was with a massive pendulum. Since we were following in his footsteps, that’s the way we went, too. Max lowered Andy down half a length of rope. From there Andy moved initially right, to build momentum, before swinging back left in a huge arc, bounding across the rock with his feet and clawing with his hands for a suitable hold to prevent him returning whence he’d come. It took Harding five swings to find the hold he was looking for at the left extremity of the pendulum, and it took Andy much the same. But he made it, to a chorus of shouts from those watching through telescopes down in the valley. From there a crack system led up to a belay at similar height to ours.

It was Max’s turn. Near disaster followed. Max had inadvertently attached his jumars upside down and failed to employ his GriGri. Facing downwards, the jumars are prone to detach. And without a backup belay device, Max had no second line of defence. He would have fallen to his death. Halfway across the traverse Andy realised the twin errors.

Later he admitted his instinct was to cry out, but instead he calmly . very calmly . asked Max to attach the GriGri and then reverse the jumars.

A close call.

Next I lowered off the haul bag, and lastly myself, running my trailing rope through an available mallion. Despite the near miss, we had completed one of the major obstacles of the Nose with great efficiency.

The eighteenth pitch included another pendulum. This time I had some fun, imitating Andy by skipping across the rock in huge leaping strides to catch a loop of rope thrown by Max. In contrast to the great king-sized original, Andy mockingly dubbed my effort ‘Charles’s Princess Swing’.

A significant change had occurred. We were now thoroughly enjoying this climb. Fear and intimidation had given way to respect, but also fun.

Halfway across the nineteenth pitch, in the so-called Grey Band, we decided to make camp for the night. This was to be the most spectacular bivouac of them all. The portaledge was suspended against the perfectly sheer wall, rather like a VIP box at the opera, jutting over the stage. It was the proverbial view to die for – although I was increasingly of the view that we weren’t actually going to die.

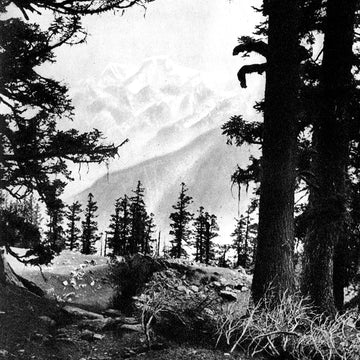

The setting sun caught the cliffs opposite, bathing them in that warm glow that comes particularly at the end of the day. Now that we were so much higher, the trees in the valley appeared like the toy foliage used by architects to enliven their model constructions.

There was an unreal feeling about the whole thing. As we gazed into the valley over dinner, the rising moon and another base jumper together provided son et lumière entertainment. Our confidence in achieving our goal was growing. Spirits were high.

We awoke well rested, and munched the remainder of our muesli while trying not to think about the date: Friday 13th. Leaving the haul bag on a ledge, we took an easy traverse left to what is called Camp IV, and from there climbed to a stance overhung by the Nose’s best-known feature, the Great Roof.

Harding had expected this to be the crux of his climb, but in fact had tamed it with relative ease. We would make similarly light work of it. Yet the majesty of the Great Roof remained. It was spectacular. Andy followed the crack line beneath the roof, which had lots of abandoned tat to aid his way.

There was one demanding long reach right, but with that overcome, he comfortably made it to an airy stance beyond the huge overhang. The Kirkpatrick brain had figured out that between the haul rope and the surplus lead rope, we had enough to drag our haul bag from its ledge at our last bivouac all the way to the top of the Great Roof in one superefficient lift. And that’s what we did.

The British pair behind subsequently tried the same, resulting in a jammed haul bag and an epic effort to free it. Why the different outcomes? I have no idea. There is art and mystery as well as science in this work.

Two further pitches, including the Pancake Flake, brought us to a sort of pulpit, Camp V; and another two, up a very straight chimney system, to the imaginatively named Camp VI. This, our fourth bivvy, was a reasonable ledge, but jammed into a somewhat darkened corner.

Max and I again took the portaledge while Andy lay on a rock ledge beneath. Wedged tight into his cramped billet, Andy reflected, ‘I think I’m an indoor person.' Wonderful, coming from the author of Psychovertical and Cold Wars.

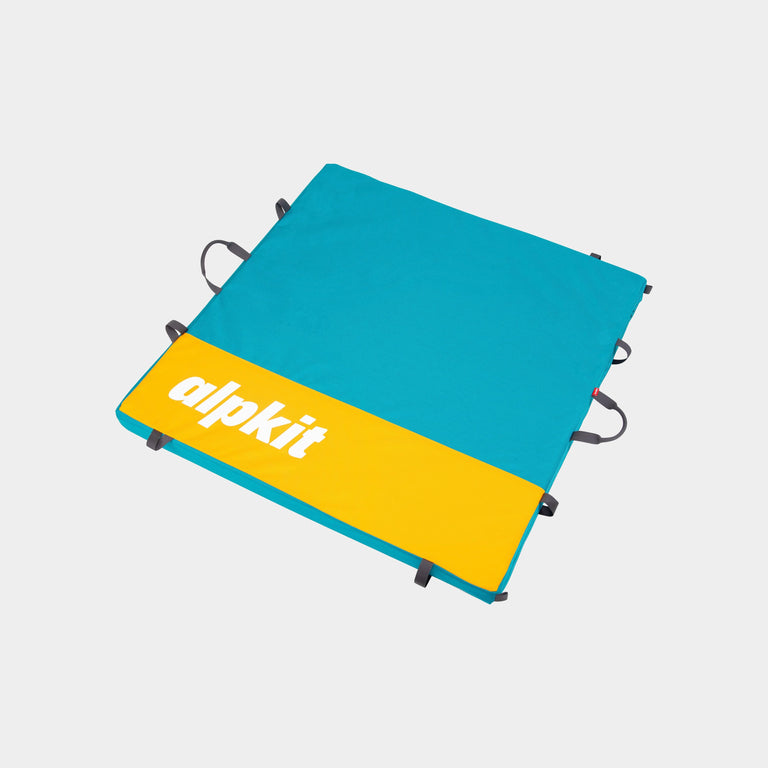

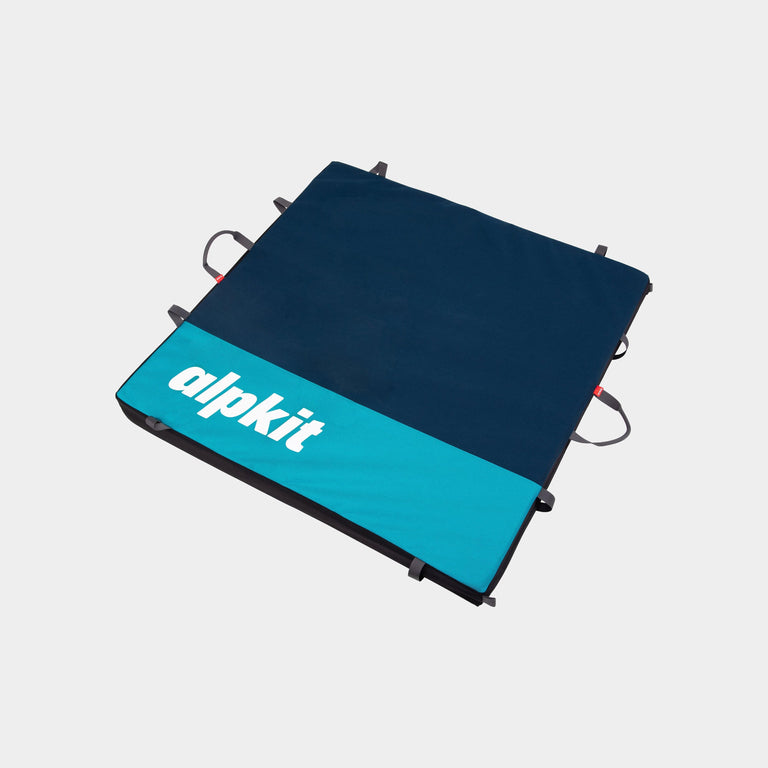

Life on a portaledge is not an entirely easy one. For a start everything must be attached: mattress, bivvy bag, sleeping bag, water bottle, pee bottle, headlamp, shoes, gloves, spare clothing . Anything that isn’t attached is likely to be lost and might well be a danger to those below.

But, once familiar, the portaledge is actually quite comfortable, and I certainly slept well. Rather better than Andy did!