The shining mountain by Peter Boardman - a tribute to the legendary mountaineer and his enduring spirit.

What you are about to read is an exclusive extract from the book 'The Shining Mountain' by Peter Boardman. To see more books we love and books that caught our eye, look at our book shelf.

You can purchase this book here on Vertebrate Publishing website.

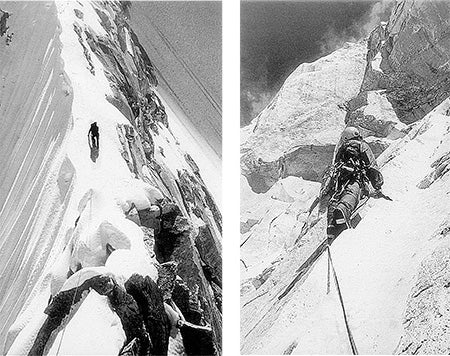

The morning of the 23rd September was clear and still. We slept past the alarm, but still managed to move away by 8.00 a.m. I set off, jumaring first. The previous evening I had tied the two ropes knotted together below the Balcony on to the soft metal piton I had tapped behind the flake. This, I had hoped, would make it easy to ascend diagonally. As I was halfway up Joe’s frayed, old, yellow rope, there was a little jerk and I somersaulted backwards. ‘God, the rope’s snapped,’ I thought, ‘I’m dead.’ Rock was hurtling past and I glimpsed the glacier 2,000 feet below. Then the rope began to tighten and stretch and spun me round into an upright position till I was yo-yoing up and down, hanging out from the Wall around the corner from the Balcony. At first I did not know what had happened. I gasped and then took brief breaths, looking wildly around me. The rope was still attached above me – the jumars had bitten deep into it, but the protective sheath was still uncut. ‘I should be all right,’ I thought. The knot on the rope above me had held, and so had Joe’s old ropes. I looked up, along the line of the rope, trying to find the reason for the twenty-foot swinging fall. The peg behind the flake had come out. ‘My fault,’ I thought, ‘I put it in.’ Still, it had held my weight the previous day. ‘Thank God I didn’t fall on the eight-millimetre terylene,’ I thought, ‘even if it hadn’t snapped, the jumars would have sliced straight through it.’ At that moment Joe appeared around the corner, lower down the fixed ropes, about a hundred feet away.

‘You’re going slowly today. What are you doing over there?’ he shouted.

‘Oh, I just thought I’d go for a swing over this wall and see what it was like,’ I said. ‘The peg I put in halfway up to the Balcony coming out, helped me.’

‘Christ,’ said Joe. ‘I thought I heard a little yelp and a clatter. Can you get back from there?’

‘I can as long as the rope doesn’t snap.’

Fun is closely linked to fear. I began to slide the jumars slowly up the rope, trying to avoid any sudden sharp movement. After fifty feet I was on the Balcony. It had taken two and a half hours to reach it from the camp. The uncontrolled feeling of being flung about helplessly that the accident had brought, had shaken me – avalanches, falls, cars rolling, I had experienced them all in the past. Death could so easily follow that. The barrier of overhangs now stretched far out above our heads.

Over on our left, the overhang jutted out fifty feet from the Wall. The only line through it was an overhanging groove a hundred feet high. We couldn’t see if there was a crack in the back of it all the way, and doubted if we had the equipment to climb it. It would be all artificial climbing and might take us an exhausting two days. The only hope was to the right.

I racked a lot of equipment to my harness and dumped my sack on the Balcony next to Joe. It was difficult to decide what, and how much, to take. If I took too much, I would exhaust myself carrying all the weight and would be unable to do any free climbing – if some were necessary. Suppressing a knot of fear in my stomach, I moved to the edge of the Balcony. The exit from the Balcony was guarded by a seemingly detached block about four feet square. I had to use it. I slid a long knife blade piton in a crack that lay at the top of it, attached a long sling to it, and leant tentatively on it. It held. I leant on it with more confidence and looked around the corner. Below, the white hard granite swept downwards without a break or a feature to halt the eye. It bowed beneath me and I could not see where it eventually merged with the lower icefields that swept across the wall in curving bands. From here I could look right across the entire West Wall, to the South West Ridge. Great bold sweeps of rock with hidden amphitheatres and great barriers of icicles, hundreds of feet long, confronted me. I squinted at them, for the sun was moving over the South West Ridge into a powder-blue sky. ‘Good, it’ll warm up soon,’ I thought.

I peered up at the overhangs above me. There seemed to be a ramp line that stretched diagonally right and upwards intermittently through a series of stepped roofs. The whole structure consisted of suspended blocks of granite on top of each other. I looked back at Joe, ‘There’s some sort of line up there, sort of solid but detached.’

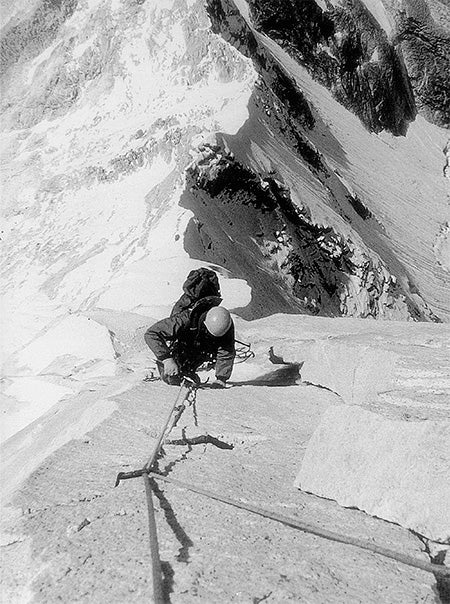

I tapped a one-inch knife blade into a crack just over the edge of the first roof and clipped an etrier into it. I put my foot into it and gently gave it my weight, looking downwards and hunching my shoulders under my helmet in case the peg came out and smashed into me. I hopped in the etriers, it still held. So I launched out up the rungs of the etriers and pulled over the edge of the roof feeling very vulnerable. The first peg is always the worst – if it had come out I would have smashed my back on the Balcony. That sort of injury would have brought complications, for we were without the helicopter safety network that exists in crowded mountain areas. From the peg I made two strenuous free moves and locked myself into a little niche in the overhangs by wedging my knees on one side of it, and my back against the other side. I was about fifteen feet above Joe, but could only see his feet from where I was, for his head was hidden by overhangs.

I was in the sunshine, but Joe was in icy shadows. Because of how he was tied onto the belay, he couldn’t move into the sun. I saw one foot stretch out into the sunlight, then the other. He was trying to warm them up! He was painfully cold:

‘Over and over again I asked myself what I was doing there, and made another promise that this would be the last time.’

I was facing the wrong way though managed to twist painfully around and place another piton, just over the tip of the overhang above my head. At full stretch I patted it in, timidly. I had a morbid fear that the whole overhang would collapse with me if I shook it too hard. How did I know it would not? Nobody had been there before!

From there a sloping, uneven ramp, a foot wide, stretched upwards across the leaning Wall. It was plastered by white ice that was stacked along it, smoothing it flush against the Wall. Leaning out on the piton I started trying to smash the ice off with my axe. It was hard work. I hacked until my arms were exhausted and I could hardly open my fingers or lift the adze, panted until some strength returned, then started again. Eventually the hard ice at the back of the ramp came away and I managed to place a piton in it. This I pounded in as hard as I could, then used it to gain some height. Two more pitons higher up, the ramp stopped for a couple of feet and then bulged out again. Holding myself in balance with one foot on the ramp and one braced against the Wall, I reached across to where the ramp started again. The ice was too far away and seemed too hard to smash off. My mind was working quickly, absorbing all the tiny details around me, bringing movements into slow motion. In the white granite in front of my eyes were particles of clear quartz, silvery muscovite and jet black tourmaline. My attention floated to them; they emphasised my insignificance – emphasised the fact that I was fragile, warm-blooded and living, clinging to the side of this steep, inhospitable world.

My mind jerked back to the situation. There was only one thing to do. I leant across and hooked the pick of my ice hammer on the start of the ice, attached my etrier to it and began to ease my weight across into it. It was a long stretch, and I knew if I lost my balance the resulting sudden movements would pull the hammer off and probably some pitons as well. ‘Watch the rope, Joe,’ I shouted. He could have been a thousand miles away. ‘If I fall now,’ I thought, I’ll swing right out into space and have quite a job getting back onto the rock – if I’ve the energy.’ The hammer held. I put an ice screw in, above the hammer. It went in four inches. I tied it off before putting my weight onto it. I could see a foothold, the first one on the pitch; it was no bigger than the top of an egg cup. On my fingers, scrabbling for holds, I made two moves across and got my weight over it. If I was careful, I could rest and assess the situation.

What a place! I looked at my watch – I had been climbing for two hours and was bathed in sweat, although the rock and the air were cold. It had been some of the hardest climbing I had ever done. The air was soundless, emphasising the loneliness of my situation. Where would I go from here? Fifty feet above me I could see the massive detached block we had seen hanging below the icefield when we had examined the Face through binoculars from Advance Camp. We had called it ‘the Guillotine’. No, not up there. The angle of the Wall had eased just off the vertical, and I carefully traversed for fifteen feet to the right, pain in my worn finger-ends forgotten, submerged in action. The rock became crumbly, and I had great difficulty in placing the only pegs I had left. I hammered in a nut, after excavating a little crack for it with my hammer, tied the rope off and shouted down, ‘O.K., Joe, come on. I’m there. Or somewhere. Gently does it.’ I was standing on one tiny foothold and my leg muscles were exhausted and quivery. I tied a couple of long slings to the pegs and stood in them.

Drained, but deeply satisfied, I hung there. It had been a struggle but I had made some progress – and was it not a struggle that I was seeking? Here, there were no spectators, none of that inflated, blown-up feeling of having everything filmed and recorded that there had been on Everest. The mountain was challenging our tenacity – but we would not give in.

Joe swung around the corner alarmingly. He was carrying an enormous sackful of gear that must have weighed fifty pounds. ‘I hope those pegs hold,’ I thought. Part of me wanted recognition for the piece of climbing I had done.

‘Sorry it took me such a long time,’ I said, as he came across to the peg where I was hanging. Half of me meant that – the other half was fishing for a compliment.

‘It must have been quite hard,’ he said.

No, we couldn’t share out fears or achievements on this climb, we had to have a business relationship. If we opened up our relationship whilst on the climb, the mountain might exploit our weaknesses. We must present a united front against the mountain and swallow the subtleties of interaction. Self-preservation had to come first, even if this made us cruelly unsympathetic. Looking after my own life was evolving as a full-time occupation. I was tired, but did not offer Joe the lead. The icefield was in the top of my mind and I wanted to reach it.

It was a complicated manoeuvre, changing over the belay with Joe, making sure, checking and counter-checking that each of us was still clipped on, and none of our equipment was in danger of falling off. The struggle, the sun, the situation and the altitude had dazed us into a dream. But the discipline within me recognised that this was the time a mistake could be made.

There was a groove above the belay, and I started up that. It seemed to dwindle out in the overhanging wall in the direction of the Guillotine. After twenty feet of straightforward artificial climbing, I thought I could see a line of weakness high on the right, where the foot of the icefield plunged over the wall in an enormous Icicle. I was climbing on a rib parallel with it. If I could reach the Icicle, climb the rock next to it, and then climb back onto the ice where it swept over the edge, then there might be a possibility of reaching the icefield. But to reach the Icicle I would have to tension down and commit myself to a long pitch. There was no time for that, the rock was already reddening with the sinking sun and we had to sort out the fixed rope through the overhangs. I clipped my rope through a karabiner to my high point and lowered myself down to Joe.

‘You’re missing some good atmospheric effects,’ said Joe.

I looked around and saw the mist billowing around the Wall. ‘We’d better get down,’ I said. We tied the rope off in six places on the pitch. ‘It’ll be a grip going up and down through that lot, with all those pegs, knots and krabs in the way,’ I said.

‘Yeah, a real Toni Kurz pitch,’ said Joe.

Toni Kurz was the Austrian climber who died on the North Face of the Eiger in 1936. Following the successive deaths of his three companions, he managed to rope down almost into the arms of a rescue party which, due to the bad conditions, was unable to ascend a small overhang to reach him. A knot in his rope jammed in a karabiner and he died of exhaustion whilst still just out of reach. A nightmare name for a nightmare pitch.

Back in the tent, after our meal, we scribbled our daily notes. ‘Someday, I’m goin’ to get there,’ hummed Joe. A Carole King song. It was the only line either of us could ever remember. ‘I think it will be the key pitch,’ I wrote, ‘it feels a sort of psychological breakthrough for me; if that doesn’t stop me, nothing will. But things are going very slowly.’

Joe wrote: ‘It must be the hardest climbing in the Himalayas. Little niggling things seem to get on our nerves. I wish Pete was more considerate.’ Above us, the light faded off Changabang like sound receding.

![Filoment Vest [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/mens-filoment-vest-2025-outerspace.jpg?v=1771963292&width=768)

![Filoment Vest [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/filoment-vest-mens-2025-outerspace-1.jpg?v=1771963292&width=768)

![Filoment Vest [Womens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/womens-filoment-vest-2025-outerspace.jpg?v=1771963413&width=768)

![Filoment Vest [Womens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/AW25-Chamonix-JW-4299_1.jpg?v=1771963413&width=768)

![Filoment Hoody [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/AW25-Chamonix-JW-5042_2.jpg?v=1768939014&width=768)

![Filoment Hoody [Womens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/womens-filoment-2024-celestial-COLOUR-CHANGE.jpg?v=1764356431&width=768)

![Filoment Hoody [Womens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/Camping-Arran-9548_1.jpg?v=1764356431&width=768)

![Fantom [Womens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/womens-fantom-2025-lego.jpg?v=1768849527&width=768)

![Fantom [Womens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/AW25-Chamonix-JW-6769_1.jpg?v=1768849527&width=768)

![Talini [Womens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/talini-1.jpg?v=1768849600&width=768)

![Heiko [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/Heiko-Men-Location-1.jpg?v=1768849679&width=768)

![Heiko [Womens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/heiko-womens-2025-cosmos.jpg?v=1768849891&width=768)

![Heiko [Womens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/Heiko-Location-2.jpg?v=1768849891&width=768)

![Jura Mountain Smock [Womens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/jura-womens-2025-alder_d06073cb-b198-4e64-8c67-594b1ed0069e.jpg?v=1768849761&width=768)

![Jura Mountain Smock [Womens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/Alpkit-Winter-Swim-91_1__1.jpg?v=1768849761&width=768)

![Jura Mountain Smock [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/jura-mens-2025-alder.jpg?v=1768849499&width=768)

![Jura Mountain Smock [Mens]](http://eu.alpkit.com/cdn/shop/files/jura-mens-2025-alder-1.jpg?v=1768849499&width=768)