Not all bouldering mat foam is equal. Understand density ratings, foam types and why polymer quality matters more than hardness for long-lasting pads.

Foam is the most important part of your bouldering pad. Sure it may have a funky design, hardwearing fabrics and the fanciest carry system going. But if the foam's no good, you definitely don't want to fall on it!

We're foam fanatics at Alpkit. What we don't know about foam isn't worth knowing. Here's everything you'll ever need to know when choosing a bouldering mat.

Bouldering Mat Foam Explained

- Find the right balance between protection and portability

- Identify good quality foam by checking density ratings

- Open cell and closed cell foam work together for protection

- Foam specifications in our bouldering mats

- Store your mat flat to extend foam life

Find the right balance between protection and portability

In theory, the ideal foam for bouldering pads is thick, soft, high-density natural PU foam (think gymnastic crash mats at climbing walls) which absorbs energy slowly for a softer fall.

Unfortunately this foam is incredibly heavy, so we have to make a compromise. It doesn't matter how good your pad is if you can't manage to carry it to the problems! You want your foam to cushion your fall and cover lots of your landing zone, all whilst being portable and durable.

Identify good quality foam by checking density ratings

Pay close attention to the foam density of your bouldering mat. Not all foam is created equal, especially when it comes to repeatedly landing on it. Some types of foam are prone to softening much quicker than others.

Foam density tells us how durable and supportive a PU foam is. It measures mass per volume of foam, shown as kg/m³. Through flex fatigue testing, several studies have indicated that the higher the polymer density of the foam, the slower the rate of degradation and softening. A soft pad isn't as supportive and won't last as long.

Foam to avoid

Very often, foam used for portable bouldering mats contains additives which artificially harden it for its density. The result is a lighter pad that still feels hard. This sounds ace, but it comes at a cost to durability. Although the foam plus additives is technically denser, the polymer density isn't any higher. And it's the polymer density that actually counts.

This is also why the foam in your pads starts to degrade and become soft after a few years of use, whereas the foam in your bed's mattress (the same foam, fact fans) will last ten years or more. Good quality, high-density foam may be heavier and costlier, but it will last longer. Light hard foam is cheaper but will soften quickly. The weight of a mat can often be a better indication of its quality than its hardness.

Open cell and closed cell foam work together for protection

Bouldering mats use a layered foam sandwich: open cell foam on the bottom absorbs impact energy by compressing and releasing air, while closed cell foam on top distributes your weight to prevent bottoming out. In our mats, the base layer is 40-70mm of HLB22 polyether foam (19-23 kg/m³), and the top layer is 40mm of cross-linked polyethylene foam (25 kg/m³). Higher polymer density means slower degradation, so check the kg/m³ rating rather than just how firm a mat feels in the shop.

The ideal foam should be soft on small falls, but very resistant to bottoming out when you hit it from height. To make this possible in a portable, durable crash pad, we make our pads by using layers of both open and closed cell foam.

Open cell foam absorbs impact energy

Open cell foam absorbs the impact of your falls. It's a softer, lighter foam that makes up the core or bottom of your pad. If you looked at open cell foam under a microscope, you'd see that it's made up of lots of irregularly shaped 'cells' that are all linked together. These air-filled foam cells compress when you fall on them, squeezing all the air out. The sponge you'd use to wash your car (yeah, alright, we never bother either!) is made from open cell foam.

We use HLB22 polyether open cell foam in our bouldering mats. This high-grade foam has a density of 19-23 kg/m³, providing excellent shock absorption while keeping the overall weight manageable.

Closed cell foam prevents bottoming out

Closed cell foam distributes your weight across the landing surface so you don't 'bottom out' (compress the foam so much that you hit the ground through your pad). Closed cell foam is used for the top layer of your pad. It's made up of rigid, uniform cells that don't really compress when you fall on them. Foam roll mats for camping are also made from closed cell foam.

Our closed cell layer uses cross-linked polyethylene foam with a density of 25 kg/m³. Cross-linking is a molecular bonding process that makes the foam more shock absorbent and resistant to repeated compressions.

The foam sandwich provides layered protection

Two layers of foam is pretty standard, with a top layer of closed cell foam and a base of open cell. Pads designed for higher impact falls often use 3 layers of foam (closed-open-closed) to provide a second layer of protection as the risk of bottoming out is much higher.

Foam specifications in our bouldering mats

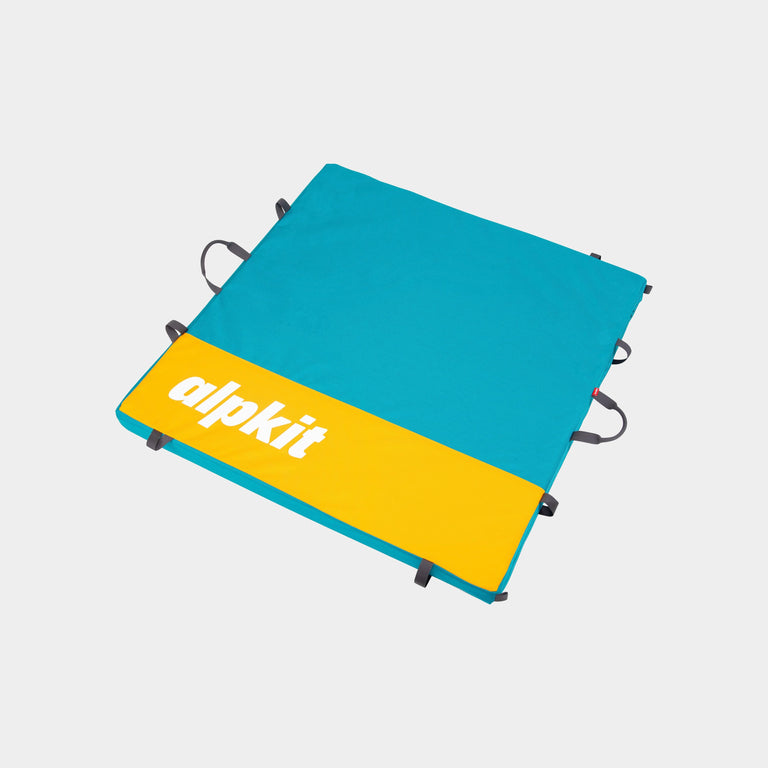

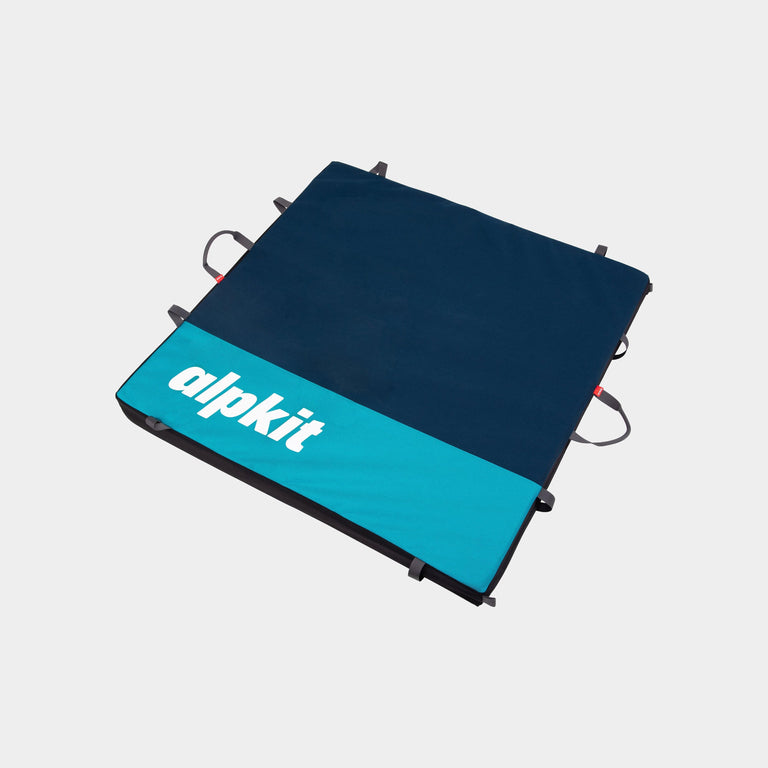

Good bouldering mats use HLB22 polyether open cell foam (19-23 kg/m³ density) paired with 25 kg/m³ cross-linked polyethylene closed cell foam. Cross-linking bonds molecules that wouldn't usually connect, making the foam more shock absorbent and resistant to compression breakdown than standard foams. All our mats are manufactured in the UK with 1100 denier Cordura covers and backed by a 25-year Alpine Bond on the shell.

We fall off things a lot, so we make crash pads that can take a lot of falls. Here's exactly what's inside our bouldering mats:

Open cell layer (base)

- Material: HLB22 polyether open cell foam

- Density: 19-23 kg/m³

- Thickness: 40mm (Phud) or 70mm (Origin, Mujo)

- Function: Absorbs impact energy from falls

Closed cell layer (top)

- Material: Cross-linked polyethylene foam

- Density: 25 kg/m³

- Thickness: 40mm across all mats

- Function: Distributes weight to prevent bottoming out

Cross-linking for durability

Our closed cell foam is cross-linked, a molecular bonding process that joins molecules which wouldn't usually link together. This makes the foam stronger, more shock absorbent, and significantly more resistant to breakdown from repeated compressions. Cross-linked foam maintains its performance characteristics far longer than standard foams.

Outer construction

The foam lives inside super abrasion-resistant 1100 denier Cordura with a DWR coating. All mat covers are sewn and reinforced with bar tack stitching in our UK factory, backed by a 25-year Alpine Bond on the cover and 3 years on the foam.

Store your mat flat to extend foam life

Make your foam last longer by storing both taco and hinge style crash pads open and flat. It's easier said than done when you're already fighting for space at home. But it's worth finding the space when the result is even more years of bouldering abuse.

Keep your mat clean and dry

Make sure your mat is clean before storing. This keeps your mat in good shape and stops it from stinking out the house. To clean your bouldering pad, wipe the cover clean with a damp rag or scrub it with a soft brush. Use a soap-based detergent to shift all the grit engrained along the stitching line without damaging the fabric.

Wet mats end up smelly and mouldy, so air dry your mat before storing it. To dry out damp foam, unzip the cover to allow the air to circulate through the foam. Never prop your mat next to a radiator or use a hair drier on it. The fluctuating temperatures could cause the foam to degrade quicker. Removing the foam is also best avoided. The foam is super durable inside its cover, but it becomes very delicate once removed. Much like a tortoise really!

Replace foam to extend mat lifespan

Extend the life of your battered bouldering mat by treating it to some new foam. Most bouldering mats allow you to carefully remove the foam. Get in touch with customer support with the dimensions of your mat for a quote. If your mat's shell also needs patching up, our Repair Station may be able to help.